From Duchamp to AI: the transformation of authorship in art

By Thomas Hajdu Director of The Sia Furler Institute, University of Adelaide.

Originally published in The Conversation.

The 19th century concept of authorship revolved around the romantic view of the artist as a lone genius. In this model, every stroke of the brush, every note played and every word written was the product of a singular creative mind, bearing the unique imprint of its creator.

However, the landscape of artistic creation began to shift dramatically with the advent of the 20th century, with artists like Marcel Duchamp, John Cage and William S. Burroughs pioneering new creative approaches such as aleatoricism, the cut-up technique and “randomness” which began recast the role of the author.

Now, AI technology looks likely to cause as much disruption as the previous revolutions combined.

Just as the artists of the last revolution grappled with their age’s social and spiritual upheavals, our artists today must rise to the challenge and engage the shock of the new that now confronts us all. AI will force artists (along with the rest of us) to examine what it means to be a “creator” and, ultimately, perhaps what it means to be human.

Disrupting the artistic landscape

Conceptual art pioneer Marcel Duchamp radically altered the artistic landscape with his work, Fountain (1917) – a urinal signed “R. Mutt”.

He argued that art wasn’t confined to traditional craftsmanship but could spring from the act of selection and presentation.

Composer John Cage took this artistic revolution a step further. His composition 4'33 (1952), where the performer remains silent for four minutes and 33 seconds, is a powerful example of a work that questions the definition of music itself. Cage’s piece isn’t just any random stretch of silence – it is art because Cage himself, a human, framed it, turning the act of listening into a creative process.

Following suit, William S. Burroughs disrupted traditional narratives with his cut-up technique, emphasising the non-linear progression of storytelling and demonstrating that authorship could extend to the reassembling of pre-existing material.

David Bowie famously used this technique for writing lyrics in some of his songs, especially in his work from the 1970s. Songs from albums like Diamond Dogs and Young Americans used cutups to create distinctive, unexpected, and often cryptic lyrics. Bowie would cut up his writings or other texts, rearrange them, and use the resulting fragments as the starting point for his songwriting. This allowed him to break free from linear thought and traditional songwriting cliches and to explore more abstract and unpredictable forms of expression.

These early disruptions laid the groundwork for today’s art and machine learning intersection. They questioned the traditional concept of authorship. Now, technology is challenging it again.

Moreover, this time around, even the role of the audience is likely to change.

Modern art

Jason M. Allen, a digital artist from Pueblo West, became one of the first creators to win a prize for AI generated art. His role was to input a text prompt into the AI tool, which then transformed it into a hyper-realistic graphic based on its training from millions of previously processed images.

In this process, Allen’s creativity came into play in formulating the correct prompts to instruct the AI, effectively guiding or curating the AI’s output.

In this case, the artist becomes a sort of co-pilot, steering the AI’s capabilities to produce a desired output. This new process raises questions about authorship and authenticity in art. It underscores how technology redefines the traditional artistic process, with artists becoming more like orchestrators of complex AI systems.

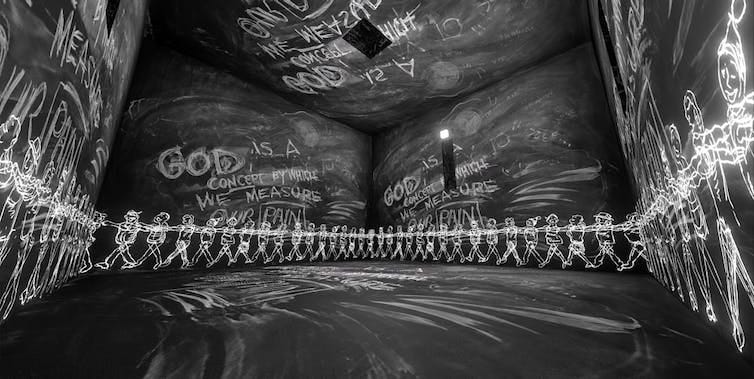

Modern artists like Laurie Anderson have begun to harness machine learning to create novel works. Anderson’s work, Scroll(2021), is a fusion of religious text and her distinctive linguistic style generated through AI.

In both of these examples, the artist functions like a curator. The manual toil of writing, drawing or composing is replaced by an iterative process of discovery, filtering and refinement of instructions to the system.

These artists are pioneering a shift in the artist’s role. Instead of being the sole creators, artists now guide, shape and direct the creative output of machine learning systems. This transition certainly presents challenges, but it also uncovers a world of new artistic competencies and opportunities.

The future

Looking to the future, we can expect the interplay of art and technology to deepen. Artists who embrace this ever-evolving landscape will contribute their unique perspectives to the development of machine learning and shape our collective relationship with it.

This time around, the revolution will also extend to the audience’s role. Passive viewers become participants in the making and remaking of the art. The very same AI systems that empower artists can empower the audience.

Read more: Art Has Always Been Artificial

Audience members can utilise AI tools to generate art, even if they do not have traditional artistic skills. AI democratises the art-making process, making it accessible to anyone with access to the technology.

This could significantly expand the art world, as more people can become creators, contributing their own perspectives and ideas. One example is a project called Tamper (2019), developed by John Underkoffler for the AMPAS, Getty and other museums. This project lets museum visitors build collages out of material taken from a museum’s collection.

We must prepare the coming generations for this rapidly changing creative landscape, fostering their ability to co-pilot with AI systems. As we move further into the age of machine learning, artists must reclaim their position at the forefront of creative thought and innovation.