The Rise of Digital Cameras: A Timeline

A quick timeline of some of the key cameras in the evolution of the digital camera

This is part 2 in a series on the rise of the digital camera. Read Part 1 here.

These days, digital photography is basically everything, capable of capturing all the colors and motion of the world around us. But there was a time when it was nothing but giant black and white dots of data being broadcast on a television screen.

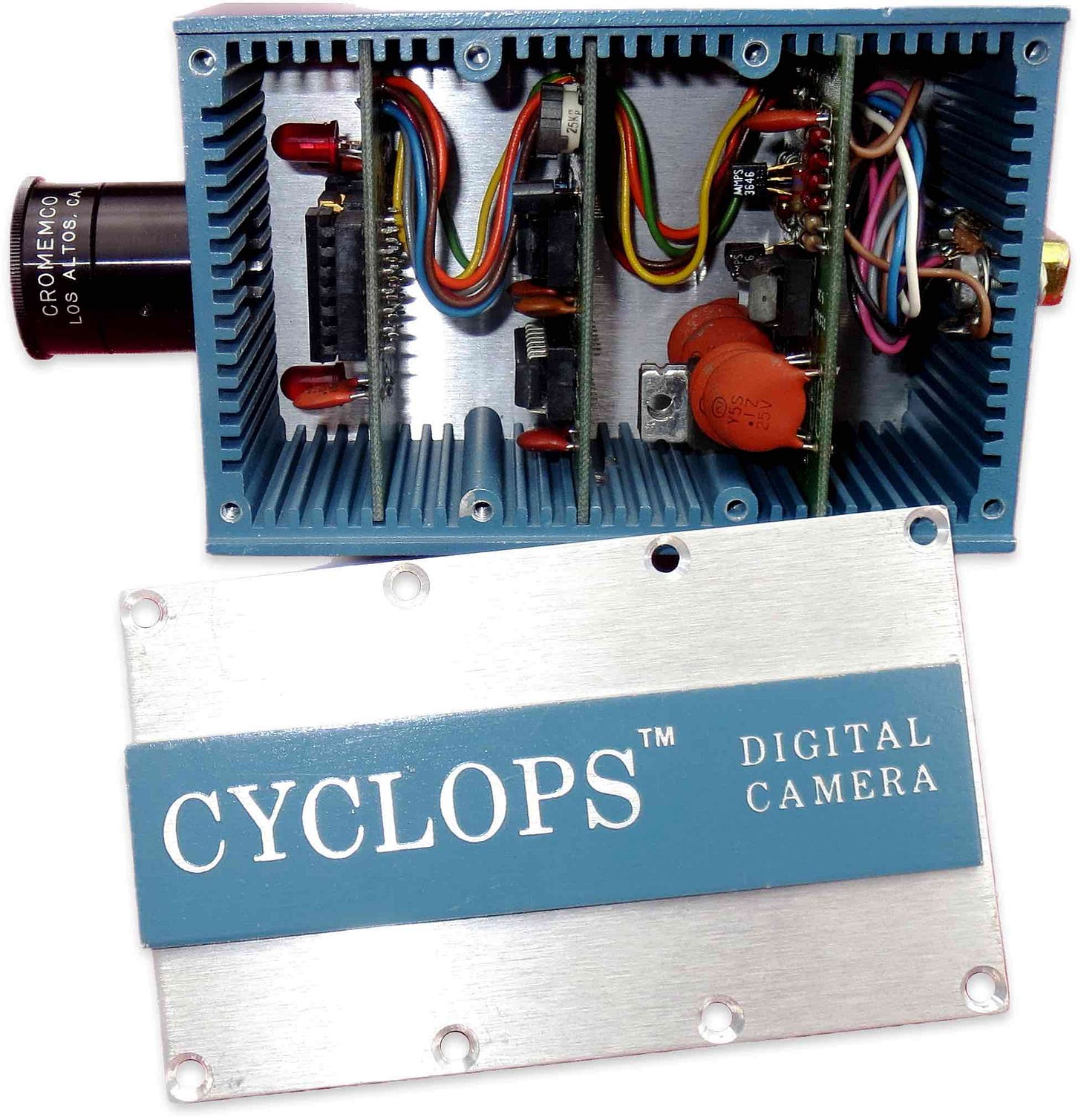

In the roughly 50 years since the 1975 release of the Cromemco Cyclops, the first all-digital camera to see commercial release, digital photography has evolved from a niche novelty to a subject of camera giant hesitation to a source of disruption to something that literally everyone has in their pocket.

The Cyclops, a 2-bit black-and-white camera that used a modified chip as a solid-state image sensor, wasn’t the first digital camera produced, however—that was a prototype developed by Steven Sasson in 1975. Sasson was an engineer at Eastman Kodak, and Kodak had a lot invested in analog photography, which meant that despite inventing a groundbreaking device, his bosses discouraged him from continuing to develop it.

“The feeling was that this was a very scary look at what could be possible in the future,” Sasson told PetaPixel last year. “As the company’s entire business model was focused around sensitized goods, proposing that they not use any of that was not popular.”

Other companies, largely in the Japanese market, did not have such hang-ups. Sony took a stab in the general direction in 1981 with the Sony Mavica, a video camera that was capable of recording still images to a removable disk, rather than film—making it the first filmless single-lens reflex (SLR) camera. While not technically digital, it was electronic, and did predict much of the convenience that would make digital cameras popular in later years. Its design suggested cameras that would be capable of recording videos just as well as still images, as many cameras now specialize in doing.

This still-video recording format became popular with news photographers who were looking for ways to speed up the process of electronic distribution, even if the cameras themselves produced lower quality works than possible with film. By the late 1980s, the technology gradually became good enough that photographers from major wire services began using them to distribute photos of major news events.

But this was not a digital camera. It was essentially an analog camera that produced digital files. True digital cameras suitable for professional use did not appear until the late 1980s and early 1990s. Kodak’s first attempt at a digital SLR, the Kodak DCS 100, appeared in 1991 and cost more than $20,000. It was only capable of shooting 1.2-megapixel photos, a resolution only barely good enough for print—a good thing, as the target audience was news photographers.

If there was any real resistance to the rise of digital photography during this era, it was mostly from the camera companies themselves, who still had legacy businesses to protect, and those who wanted to save money. (Digital cameras used to be prohibitively expensive.)

At this time, for example, Kodak’s film business was still strong, with its embrace of disposable cameras—itself somewhat belated and only in response to direct competition from Fuji—strengthening its bottom line around this period. But it would not last.

By the early 2000s, it was clear that the digital camera was going to win. The advantages of the format, often leveraging a microchip called a charge-coupled device (CCD) as an image sensor, were just too obvious, and many of them were related to the very things that scared Kodak off from initially supporting the digital camera’s development: You didn’t need film to use a digital camera, and you didn’t need prints. (Though if you wanted them, you could still get them developed.)

That meant that Kodak could never sell consumers on a Gillette razor-style model with a digital camera, and that ultimately sank Kodak’s position in the camera world.

It likely became even more surprising when the low-end consumer cameras were replaced entirely by smartphones.

This is part 2 in a series on the rise of the digital camera. Read Part 1 here.

Subscribe for Part 3:

It's still wild to consider that Kodak got in there so very early, easily grabbing the "first mover disadvantage" as they continued to double down on their legacy business instead of embracing the future. "Embracing the future" is easier said than done, and sounds overly facile in retrospect.

This is a neat little lesson.